BUKU | SAIDNA ZULFIQAR BIN TAHIR (VIKAR)

Teks penuh

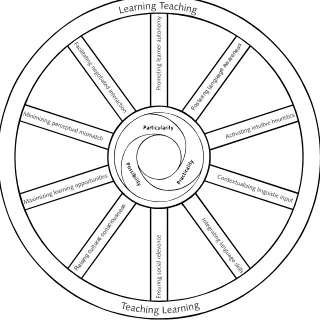

Gambar

Garis besar

Dokumen terkait

Sehubungan dengan telah selesainya masa sanggah terhadap pengumuman pemenang untuk paket pekerjaan Penyusunan Pengembangan Industri Kecil dan Industri Menengah di Kabupaten Kayong

Berdasarkan Berita Acara Penetapan Pemenang Nomor : 6/PPBJ/MEP/DISDIK/2012 tanggal 3 Oktober 2012, dengan ini kami mengumumkan pemenang..

Berdasarkan Berita Acara Penetapan Pemenang Nomor : 6/PPBJ/PRBS/DISDIK/2012 tanggal 9 Oktober 2012, dengan ini kami mengumumkan pemenang..

The measure of efficacy used in the research on hot water treatment of mangoes against fruit flies was usually failure of any larvae emerging from treated fruits to form

Paket Pekerjaan : Jasa Konsultan Pengawasan/ Supervisi Penyiapan dan Pematangan Lahan, Jalan Poros/ Penghubung, Jalan Desa, Jembatan, Gorong-gorong, Pembangunan

Berdasarkan Surat Penetapan Pemenang Lelang Nomor : 07/TAP/DPU/BM-16/POKJA/2016 tanggal 31 Mei 2016 tentang Penetapan Pemenang Lelang Paket Pekerjaan Peningkatan Jalan Simpang Jalan

Paket pekerjaan : Pengadaan Jasa Konsultansi Penyusunan Rencana Peningkatan Jalan dan Jembatan UPT1. Atas perhatian dan kerjasamanya diucapkan

DM of kiwifruit before ( ) and after ( ) ripening, plotted against initial density and showing the respective re- gression lines. Orchard 1 comprises the lower 16 data points. 3),